Attacks on the labor movement have historically manifested in several forms.[1] Some stem from the legislative sphere. For example, English industrial workers saw the right to practically even think about joining a union made illegal by the Combination Acts of 1799 and 1800.[2] Others are actual physical attacks utilizing violence and intimidation to beat workers into submission, a nearly uncountable phenomenon including events such as the Pullman Strike of 1894 and the Bread and Roses Strike of 1912. For much of US labor history, these avenues of oppression primarily targeted workers in the private sector. In the mid-20th century though, things began to change. In the wake of World War II, some states began to target public employees’ ability to go on or even approve of the idea of their union going on strike. Thirty-seven states, as well as Washington DC, have made it illegal for public workers to engage in strike efforts.[3] For the purpose of this article, the legality of such strikes in New York State is going to be the focus.

Attacks On the Right To Strike

On September 1, 1967, New York State enacted the Public Employees’ Fair Employment Act, otherwise known as the Taylor Law for its namesake George W. Taylor. This law did guarantee workers in the public sphere the right to collective bargaining, undoubtedly a good thing. However, the right to collective bargaining is presented in neutered fashion thanks to another section of this law, which bars public employees from going on strike. As stated in Article 14 Section 210 of the New York Civil Service Law, “No public employee or employee organization shall engage in a strike, and no public employee or employee organization shall cause, instigate, encourage, or condone a strike.”[4] Although all workers in the public sphere are subject to this law, it seems as though no portion of public workers have faced as much difficulty with it as public school teachers. This has affected millions of teachers, some of which will be touched upon here, but there presents a particular event for historical consideration. In October of 1971, teachers from the Frankfort-Schuyler Central School District in New York’s Mohawk Valley engaged in a brief but powerful strike.

Origins of the Strike

Leading up to the strike, teachers from the Frankfort-Schuyler district were at an impasse in their negotiations with the School Board.[5] One source claims that the impasse wasn’t reached until May, however as will be shown, this was incorrect. According to The Evening Telegram, the local paper of nearby Herkimer, NY, the impasse initially began in February. The following month, the teachers’ union, the Frankfort-Schuyler Teachers Association (FSTA), filed an unfair labor practice charge against the school board based on claims that the board refused to negotiate in good faith, the first instance of the School Board acting in antagonistic fashion against the teachers. The following May, a fact-finder was appointed by the Public Employees Relations Board (one of the more helpful prospects of the Taylor Law) in order to try to help the two parties reach a mutual compromise. This effort was to no avail. Dr. Martin Etters, the fact-finder, presented the following recommendations as listed in the newspaper:

Dr. Etters recommended a 5 percent salary for teachers which would bring base to $7,150. Other recommended changes included a $286 increment: a $143 differential for a master’s degree; an increase to $15 per graduate credit hour, a longevity increment of $286, and a 5 percent increase in payment for co-curricular positions.[6]

The recommendations continue:

Other recommendations were improvement in health insurance payments from from 100-50 percent to 100-60 percent. Substitute teachers with a B.A. degree to receive 1-200 of B.A. base salary; initiation of a program of teacher aids with half-time clerical assistance as each of the schools and a report on this experiment to be made by March 1972; and 10 days sick leave with accumulation to 165 days.

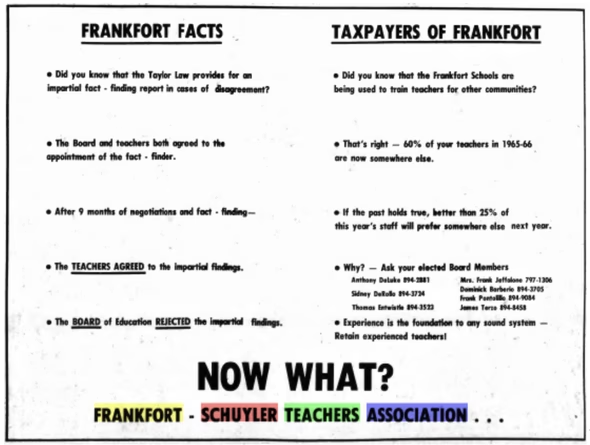

Even with the results of the fact-finder, a settlement seemed far out of reach. The School Board rejected the findings provided by an impartial researcher! The Board cited that the proposed 5 percent increase “when applied to the current schedule with built-in salary increases, would raise salaries from 8.3 percent to 11.5 percent.” The teachers on the other hand were ready to accept Dr. Etters’ proposal. This frustrating situation led the FSTA to release an ad in the October 14th edition of The Evening Telegram to shed light on the Board’s confusing rejection, utilizing what may be referred to as a revolutionary propaganda campaign to educate the people living in the district of what was really going on.[7]

After eight months in and out of a deadlock, the FSTA brought up the possibility of voting on a strike in defiance of the Taylor Law, depeding on the results of upcoming negotiations on October 7th. When the evening of the negotiation session arrived, members of the FSTA gathered outside of the Frankfort-Schuyler high school in solidarity with their negotiation team headed by Joseph Reina, president of the union, Frank Squillace of the New York State Teachers Association, and David Valentine, chief negotiator for the FSTA and member of the New Hartford Teachers Association. This meeting served not only as a time for negotiation, but as an opportunity for the union to counter the hostile narratives reportedly being perpetuated by the School Board. When addressing the teachers before entering the building, Squillace stated he wanted them to “go on and record as being 100% behind your negotiators. For months, the school board has said the teachers were not behind its negotiators. That is not true, and it is shown here tonight.” Reina highlighted the presence of around seventy-five teachers there to show support as evidence in contradiction to the School Board’s attempt to sow seeds of conflict, which represented nearly 90% of the FSTA’s membership.[8]

The October 7 meeting concluded with the teachers and the Board remaining at a standstill. In a dialectical response, the teachers’ union officially established what’s known as a “crisis center” for the union to operate during their plight. Establishing this center was cited in the news as being the second step in a six step job action plan, with the sixth step being the last resort of a strike.[9] This “crisis center” served what some may consider, as it will be considered here, a revolutionary purpose. That purpose being to “provide the public with an explanation of the various issues involved in the bogged down contract talks” as explained by Reina.[10]

Though School Board members are not necessarily members of the bourgeoisie since there’s no real matter of capital or profit in the public schooling system, they ultimately serve the bourgeoisie. This is evident in the education system overall with their upholding of the conditioning of students to fit within the borders of a “good worker,” the pro-capitalist narratives often found in classrooms, as well as in their historically consistent disputes with teachers unions and anti-labor attitudes towards them. Parallels can be drawn between the struggle of the FSTA and a struggle taken on by Mount Markham teachers of just twenty minutes away in 1975. The Mount Markham Teachers Association was charged by the School Board with utilizing “unfair labor practices” based on the claim that the teachers had been inconsistent in their negotiations, calling it a form of bad faith argumentation. The teachers responded by releasing a public statement in the local newspaper to counter the Board’s narrative in addition to questioning other claims made regarding their negotiations.

Initiate: Job Action

The FSTA’s crisis center functioned to counter a strategy of anti-labor propaganda and activism that actually originates from the Mohawk Valley. The aptly named “Mohawk Valley Formula” is a nine-point methodology for union busting and strike breaking established by James Rand Jr. during the Remington-Rand Strike of 1936-1937. It was first applied in Ilion, New York, in close proximity to the Frankfort-Schuyler district.[11] One of the methods listed in the first step of this formula of anti-union class warfare is to:

...disseminate propaganda, by means of press releases, advertisements, and the activities of ‘missionaries’, such propaganda falsely stating the issues involved in the strike so that the strikers appear to be making arbitrary demands and the real issues, such as the employer’s refusal to bargain collectively, are obscured.[12]

In an impromptu Q&A session held by the School Board, local residents came to a Board meeting to ask questions, wherein the Board gave answers designed to discredit the plight of the FSTA. This Q&A was then made public by the Evening Telegram.[13] Since this was only one facet of the Mohawk Valley Formula it would be unfair to say that the district was consciously utilizing it, but this Q&A and the media release that came of it served a similar purpose to the formula as a whole.

Besides the salary issue, the other primary demand presented by the union was a shorter working day. From the beginning, the teachers were pushing for the introduction of a seven hour and fifteen minute school day, and they were already willing to compromise as they would’ve also accepted a seven hour and thirty minute day.[14] What’s most admirable of this demand is that the FSTA demanded this change not only for their benefit, but for the students’ as well. Though it varies by state, district, and even the level of schooling, a school day in the United States typically runs for seven to eight hours five days a week. Though the proposed reduction would not have been substantial, there would still be at least minimal benefits for both parties with a shortened working day, including more time to sleep, an improved mental health state and general well-being, and a reduction in burnout among other such prospects that would make school a better environment for both students and teachers alike. One benefit specific to teachers is that they would have more time to prepare lesson plans and complete other tasks such as grading assignments.[15] Despite all of these potential benefits, the school board asserted that this was not negotiable.

Breaking Point: The Strike Cometh

Despite the tensions at hand, the FSTA hoped to avoid going on strike. Union president Joseph Reina was even quoted in one Utica newspaper as saying “We’re trying to do our best to avert a strike.” Reina additionally stated that the two parties were close to reaching a settlement on the salary issue, indicating a sense of optimism in the arbitration that a strike may very yet be avoided.[16] Though the FSTA had already sanctioned the use of a strike a few days prior, at least according to one paper, union negotiators returned to the bargaining table on October 13 to discuss the latest proposal presented by the district. The union was hopeful that the newest meeting would foster conditions that would make a strike unnecessary.[17]

This optimism was misplaced. The October 13 meeting didn’t go as one would hope, and the prospect of a strike became ever more apparent. There was still some hope of a return to negotiations, but at this point such thinking was a pipe dream. A preemptive picket line consisting of thirty-five FSTA members was even formed in the event that a strike came to fruition.[18] Negotiations officially broke off 12:10AM, October 14 after conversations became heated on multiple occasions throughout the meeting. The School Board claimed that they presented counter proposals that were close to the demands of the FSTA, but one particular point of contention was likely the catalyst for abandoning the bargaining table: payment per graduate credit hour. As it’s laid out in one newspaper;

The school district presently pays an additional $12 per graduate credit hour. FSTA is seeking $14.88 per graduate credit hour in blocks of six, and Chudy [public information officer for the union] said today the board had previously given a tentative proposal to $13.50 per hour. This offer has since been withdrawn and the board has reverted to its original $12 figure.[19]

Valentine asserted that it was the School Board who made things more complicated and broke off the negotiations. Reina likewise asserted that the FSTA acted in good faith throughout the duration of the talks. In the same newspaper, both Reina and Valentine explained that the school board acted unfairly toward not only the FSTA, but the public as well by upholding deceitful narratives. The Board’s unfairness stems from a mathematical issue concerning how the FSTA’s demands fit within the yearly budget. Firstly, Reina claimed that the budget for teachers set at the time was $943,000. The teachers association’s proposal totaled at $939,000, $4,000 less than the budget. Interestingly enough, he also pointed out that in the prior school year the district had budgeted $938,000 for teachers, however they only spent $917,000. What happened to the $21,000 surplus? Secondly, Valentine noted a second source of surplus from the previous year, shedding light on the fact that of the twenty-four new teachers hired in that period, thirteen were only at the minimum salary of $6,800. This resulted in an additional surplus of $22,000.

Contrary to Valentine’s assertion, the School Board claimed that it was the FSTA’s negotiating team who allowed arbitration to break. According to the Evening Telegram, both parties accused each other of utilizing “stalling tactics” by refusing to be the first to end the meeting. Joseph Power of the New York State Teachers Association tried to be practical and level-headed about the problem at hand, saying; “Apparently there has been a misunderstanding on both sides. The only practical thing is to adjourn.” Anthony DeLuke, a member of the district’s negotiating team, responded with vitriol. Pointing his finger and with anger in his voice, DeLuke told Power, “I am not in favor of adjourning. [Speaking to a newspaper reporter] Be sure to get that down. We didn’t break off the talks. I’m willing to stay here all night.”[20]

The Board had the gall to reject the fact-finder’s recommendations, as seen earlier, while the teachers showed that they were ready to accept this compromise and put an end to this protracted battle. The Board claimed that the rally of support held by the teachers earlier in the month and the opening of the crisis center was a “show of force” all while weaponizing their own narrative to stir ire against the teachers among taxpayers. With the stubbornness exhibited by the district, it’s no wonder that, at least according to Valentine, the district had seen a sixty percent turnover of teachers in the five to six years prior to these events.[21]

Officially On Strike

Called at 1:30AM, the FSTA was officially on strike as of 7:30AM, October 15. Leaders recognized this was a risky move given that public employees are barred from striking. Reina stated: “I’ll go to jail for what I think is right.”[22] The teachers association was even served with a court injunction instructing them “not to strike” and “not to picket.” The FSTA however would not be deterred. They stood ready to negotiate with an authorized team or board representatives, but for the time being they would withdraw their services from the schools and uphold the picket line. Pickets patrolled the entrance of each school building in the district, a method of ensuring that their voices would be heard and their right to fight would not be denied.

The effects of the strike permeated immediately. One of the district’s high schools and a middle school were forced to close, though the two grade schools stayed open. The strike officially began on Friday. The teachers paused their picket during the weekend but resumed the following Monday. The district superintendent, Andrew Mulligan, reacted to this mass absence by ensuring that the elementary schools were fully staffed through, at least in part, scab labor. To quote: “A total of nine teachers and 45 substitute teachers reported to work, and we have both of our elementary schools fully staffed.”[23]

A testament to how badly the FSTA wanted a solution, the first day after pickets began the union sent another proposal for a settlement of the salary issue. The union proposed raising the base salary for new teachers up to $7,000, just $200 more than the starting salary at the time. Of course, in their antagonistic fashion, the district rejected this proposal just as they did that of the fact-finder. The teachers association asserted that on top of monetary issues, they were still fighting for other concerns such as the shorter work day, an increase in sick leave, and the hiring of four additional teachers aides to cover tasks such as cafeteria duty in two of the school buildings.[24] Superintendent Mulligan claimed that these issues had been dropped the previous Wednesday, thus the district refused to speak on them again. The teachers reportedly tried to bring these issues back to the table, but the district refused to consider them. Though the district remained antagonistic, there were two major forces standing behind the Frankfort-Schuyler teachers.

The first major force was the material conditions. For much of the time that the Frankfort-Schuyler teachers engaged in their struggle, teachers from the Utica school district engaged in their own fight, which had only recently been resolved on October 16.[25] As the struggle in nearby Utica ended, the struggle of the FSTA continued and others would arise. As explained in a speech given by Emanuel Kafka, president of the New York State Teachers Association, there stood the potential for upwards of a dozen more school districts to be engrossed in disputes. He was especially optimistic about the struggle in the Frankfort-Schuyler district. Building upon this, Kafka explained that the NYSTA would support the striking teachers in any way possible. To quote, “You are the seventh association to take action. The 94 percent of your teachers who stayed out yesterday is the highest percentage in the state. I’d like to see it raised to 100 percent on Monday.” Kafka continued, “We will help you through staff, counseling, and financial resources if necessary.”[26]

The End: A Settlement Is Reached

Still optimistic for a settlement, FSTA officials held hope that the help of the Public Employees Relation Board would aid in reaching a final resolution. Unfortunately, the PERB’s moderator, Henry Ford, was forced to drop out of the talks. Ford cited his failure to get the two parties to reach agreement in addition to important personal business as his reasons for leaving the scene.[27] That a second state-appointed agent was unable to aid in finding a settlement is yet another testament to the district’s stubbornness and the difficulties that they imposed in these negotiations.

All that said, a meeting between the teachers and the district was scheduled for the following Tuesday according to district officials. Adding to the tension, that coming Wednesday a hearing before a member of the State Supreme Court was scheduled in order to determine if the FSTA should face legal repercussions for ignoring the anti-striking order.

Apparently though, these problems were not deterrents, as the FSTA and the district finally reached a tentative agreement very early that Tuesday morning. Teachers returned to their classrooms that same day.[28] After some further deliberation, the district’s Board of Education voted to ratify the contract 6-1, with a “no reprisal” clause, otherwise known as a no retaliation clause, introduced by the teachers being ratified in a vote of 5-2 as well. The FSTA’s fight brought about several positive changes in this new contract. Prospects of this contract included raising the base salary for new teachers up to $7,000 a year, multiplying other salaries from the 1970-1971 contract by 105.75 percent, teachers with a bachelor’s degree received $7,995 for the 1971-1972 contract and those with a master’s received $8,718. Other new developments included an increase in the district’s coverage of insurance premiums for any of the teachers’ dependents and a raise in payments for teachers’ graduate credits up to $13.50 per credit hour. It appears that the district wound up following the recommendations presented by the fact-finder after all.[29]

Reportedly, the teachers were still required to appear in court due to the anti-striking order unless the district retracted the restraining order. Based on all the available information, as well as the fact that no further news coverage has been found covering any sort of court proceedings, it’s speculated that the restraining order was withdrawn. This strike only officially happened for two days, but the Frankfort-Schuyler teachers emphasized that through solidarity and cooperation, in addition to defiance against unjust legislation, their struggle was a righteous one, and a battle that defied the capitalist legal system, even if they didn’t know it.

On The Right to Strike: Those Against It

As touched upon earlier, public employees and any organization representing them in the state of New York are barred from engaging in or promoting strike activities as a result of the Taylor Law. Opinions on the Taylor Law and teachers’ right to strike were greatly divided in the Mohawk Valley, as well as the state in general, at the time of the Frankfort-Schuyler Teachers Strike, and still are to this day.

Utica newspaper The Daily Press released an editorial condemning not only the strike of the FSTA, but the struggles in nearby Utica and Rome earlier that month. In essence, the article defended the school boards by claiming teachers failed to take responsibility or accountability for how negotiations became so protracted. The article in general is extremely dismissive of the FSTA strike, effectively insulting the intelligence of the teachers and bolstering the narrative that unions are greedy and unreasonable in their demands. Accusations of being unreasonable are pronounced in the fact that the paper cited high taxes and the rate of unemployment in the area at the time in conjunction with the union’s call for higher pay as an example of the teachers' supposed ignorance and corruption. To quote a relatively lengthy passage from the article:

Most of the contracts have been in negotiation for six months or longer, and some strike sympathizers read this to mean that the school boards are unduly stubborn or they would have reached agreement by this time. This is a two-way street, however. It is not up to any school board to give in simply because six months or more have passed without reaching an agreement. The teachers have an equal responsibility in reaching a compromise. The third strike [i.e. Frankfort-Schuyler] also suggests that teachers as a group are asking more than school boards are able to pay. It is almost as though the teachers do not realize that times have changed quite radically in the past year or two.[30]

The paper finished their article by saying that the strikers, in their defiance of the Taylor Law and the Supreme Court order, set a poor example for their students. To quote: “...these strikers are entrusted with teaching children the difference between right and wrong and what is legal and illegal.”[31] The paper also argued that the Taylor Law should be toughened to further suppress public employees.

Concerning the question of money, two days before this article was published, The Evening Telegram published an article wherein Reina explained the surplus of money the district already had that they were refusing to use for the new contract. There was no expectation of placing any further burden on their fellow workers, the FSTA just wanted the district to actually use the money they already had. Secondly, regarding being a poor example for the students, this accusation is built entirely on the foundation of law and order politics espoused by the likes of Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan. Is this not what the teachers were doing in their fight? What is legal is not always right and what is illegal is not always wrong. The teachers showed the students the meaning of justice in their defiance of an unjust law and their determination to remain strong in what they fought for. The argument presented is based entirely in a legalistic fallacy posing as a moral victory against the teachers. Also, of course, do parents not play a more direct role in teaching lessons like these? Finally, calling for the Taylor Law to become even more strict is wholly anti-worker in nature and only increases the danger that public employees would face in exhibiting their grievances with their employers. How should it be made tougher? Threats of mass arrest and police violence simply for wanting better insurance coverage? The Taylor Law already uses dues deductions, fines, and potential jail time for union leaders.

One of the primary reasons people oppose teachers strikes, as well as public worker strikes in general, is that such work is too important for the function of a community and society as a whole. Thus, if public employees were to go on strike, society as a whole is put in danger. John Martin Rich of the Iowa State University summarizes this opposition as “to strike is unprofessional.” Rich points out that the severity of the strike’s harm on society completely varies based on what sector of public employees is on strike. To quote:

To assume that the harm produced by a strike of publicly-employed city auditors would be as great as a strike of publicly-employed garbage collectors would be erroneous. To say that the social harm of a strike by public school teachers would be as great as that of a strike by policemen would be unrealistic.[32]

The anti-strike position against public employees that seems to make the most sense, at least from the outside looking in, is touched upon in a March 1969 edition of the journal Monthly Labor Review. Anne M. Ross explains: “Those opposed to stoppages point out that the strike, as an economic weapon, is inapplicable since government will not be put out of business, nor will it use a tactic such as the lockout.”[33] Of course, this is likely a position held by higher ups and supervisors in the public sphere. The only sensible anti-strike position of course is to refrain from engaging in one for tactical reasons, so long as this is the position of the union in particular.

On The Right to Strike: Defending It

Some have opposed the Taylor Law from a moralistic approach. One Reverend Gerald Toner, labor relations theologian for Boston College at the time, viewed the Taylor Law and others like it as immoral. In a talk given to the striking teachers in nearby Utica, Father Toner asserted that both the Catholic and the Protestant church demanded the right to strike for all workers, saying that “Collective bargaining without the right to strike is like a man without his legs – he can’t walk.”[34] Toner vocally advocated for the right of public employees in all facets, for better or for worse, to go on strike, with teachers being one of those groups who should be guaranteed that right.

John Martin Rich makes an interesting case for teachers strikes, and by extension all public employee strikes, to be considered acts of civil disobedience, on the basis that their typically peaceful proceedings act in defiance of legal statutes. Rich explains;

We give the name civil disobedience to acts which share certain characteristics. One characteristic is that of nonviolence to persons or property. Felonies, for example, usually though not always utilize or result in some form of violence. Civil disobedience is a form of public protest, an act which is designed not to destroy but to correct what the dissenters believe to be an injustice. Teacher strikes, when they violate existing laws and when they fulfill the criteria of civil disobedience described herein, are acts of civil disobedience.[35]

Though there do exist revolutionary characteristics of civil disobedience such as that of the US civil rights movement, Rich constricts his definition to one within a liberal framework that calls acts of civil disobedience incompatible with revolution. Similarly, Rich brings up that teacher strikes can be morally justifiable based on the premise of the vastly differing impacts that a teachers strike and a firefighters strike would have on societal functions, bringing his analysis into the same moralistic framework that Toner does.[36] Rich concludes:

…teachers should use legal protests to correct injustices whenever possible; however, in those cases where all legal alternatives have been tried and exhausted, justification could be based on the moral rightness of the strike by calling to public attention the existing injustices, the exhaustion of legal alternatives, and the predicted correction of injustices by striking.[37]

The aforementioned Anne M. Ross mentions a pragmatic approach to opposing legislation like that of the Taylor Law in her article. Ross cites the critique that by implementing strike bans, collective bargaining itself is placed under attack and is thus greatly impeded. With the right to strike denied, there exists no real power behind the unions in their negotiations with employers. School, government, and other public officials are able to take advantage of this lack of proletarian power by further neglecting the needs of their employees and utilizing bad faith methods of arbitration.[38] Even if public workers choose not to go on strike, still having that power in their back pockets aids in keeping negotiations on the proper track and, potentially, prevents further work stoppages. Will a strike always be the first result of a labor dispute? Probably not. But to actually have the right to strike is of the utmost importance. To be able to strike is to be able to properly exercise collective bargaining, and vice versa. Solutions proposed in this argument include removing no-strike clauses from union contracts and introducing legislation that protects the right to strike for all workers.

Moralistic, legalistic arguments against anti-labor legislation such as Toner’s and Rich’s, though appreciated, often fall short due to how morals differ between groups and whether or not these morals are connected to material conditions. The same goes with what people believe should be considered legal in the various spheres of legislation. The pragmatic opposition examined by Ross makes sense when working in a frame of reformism or incrementalism, but it ultimately fails to properly address such attacks on the working class, a revolutionary approach needs to be taken.

Conclusion: The Fight Today

In a pamphlet from 1899, Vladimir Lenin espouses the foundational importance of striking for workers in all sectors. A few particularly relevant quotes from this piece includes the following:

As long as workers have to deal with capitalists [in our case, the Board of Education] on an individual basis they remain veritable slaves who must work continuously to profit another in order to obtain a crust of bread, who must ever remain docile and inarticulate hired servants. But when the workers state their demands jointly and refuse to submit to the money-bags [school board], they cease to be slaves, they become human beings, they begin to demand that their labor should not only serve to enrich a handful of idlers, but should also enable those who work to live like human beings. Every strike reminds the workers that their position is not hopeless, that they are not alone. A strike, moreover, opens the eyes of the workers to the nature, not only of the capitalists, but of the government and the laws as well.[39]

Under the thumb of capitalism, strikes hold an inherently emancipatory and thus revolutionary character. Even when met with defeat, strikes provide an opportunity for workers to challenge the capitalist apparatus, at least in as limited of a capacity as a movement can when forced to operate in the framework of capitalism. Strikes and work stoppages, as stated by Alex Gourevitch, function as a response to the oppressive workplace structure upheld by capitalism, an act of rebellion wherein workers are able to refuse the one thing demanded of them, the one thing drilled into their heads as their purpose for living: work. Additionally, strikes give the proletariat the chance to fight for and exercise freedoms previously unknown to them. Gourevitch explains:

As responses to oppression, strikes are acts whereby workers seek to claim some piece of the freedom that they are denied. They claim that freedom either by winning new freedoms, by exercising the very freedoms they are usually denied, or both. Strikes are therefore complex acts of self-emancipation.[40]

Besides the freedom of simply biting back at the capitalists and their agents, workers are given the opportunity to display that at the core of things, it’s not the workers who need the factory owners, it’s those owners who need the workers. This is done through displays of community and camaraderie in conjunction with a sense of self-reliance. During a strike, the workers are more explicitly the masters of their own fate. Decisions on whether or not to accept a settlement and return to work, who does what during a strike, etc. uphold a revolutionary, emancipatory stance in their fight. Utilizing mutual aid, working with the community in various forms (mutual aid, education, even charity), provide workers with an autonomy unknown to them when they’re forced to stand behind a cash register or CNC machine for eight to ten hours a day.[41]

Defending the right to strike has proven crucial in the modern day. According to the magazine Mother Jones for example, there have been over eight-hundred teachers strikes in the United States between 1968 and 2012.[42] As the faults of capitalism have become more apparent for the working class in the twenty-first century, teachers strikes have simultaneously become more prominent in the US and placed under further scrutiny by reactionary forces. Though times have changed and methods have developed, the motivations of teacher strikes nowadays mirror the motivations of the Frankfort-Schuyler teachers in 1971; better pay, better benefits, and better prospects for not only future teachers but their students as well. In 2018 there was a mass revolt of teachers from various states, including Colorado, Arizona, Kentucky, Oklahoma, and others demanding higher pay for themselves and other school staff in addition to better funding for education in general. These mass walkouts and protests were met with great support.[43]

A 2018 report from NPR reveals that fifty-nine percent of teachers in the US have worked a second job either during summer break or during the school year, and eight out of ten have had to pay for school supplies with money from their own pockets. A survey from the app Fishbowl in 2019 found that of the teachers who answered, forty-nine percent said that they’d worked secondary jobs during either of the two periods.[44] One 2019 report indicates that teachers have spent an average of $459 of their own money for classroom supplies since 2011. Additionally, a more recent piece states that teachers have been placed in situations where they had to pay, depending on what materials are necessary for which subject, costing up to $6,000 a year.[45] Though a more explicit structural change (i.e. the destruction of capitalism) is necessary to truly be rid of these problems, in the short term these troubles can be addressed by militant action from unions.

There are reports, contrary to notions that teacher strikes harm students and only cause more problems, proving that teacher strikes hold far more benefit than detriment. Based on data published by the education group Accelerate, ninety percent of teachers strikes between 2007 and 2023 across twenty seven different states demanded higher wages and better benefits, with over fifty percent of strikes calling for improved working conditions such as smaller sized classes and a generally increased investment in the quality of schooling. Strikes on average were found to have helped those demands be met. Furthermore, this study found that teachers strikes typically caused little if any academic harm to students. To quote:

Previous research on teacher strikes in Argentina, Canada, and Belgium, where work stoppages lasted much longer, found large negative effects on student achievement from teacher strikes. (In the Argentina study, the average student lost 88 school days.) In contrast, the researchers find no evidence that US teacher strikes, which are much shorter, affected reading or math achievement for students in the year of the strike, or in the five years after. While US strikes last two or more weeks negatively affected math achievement in both the year of the strike and the year after, scores rebounded for students after that.[46]

The fight against the Taylor Law is still ongoing. Since early 2023 there has been a proposed bill floating in the New York State Assembly, Assembly Bill A906, that if passed would consider the ability of all workers to go on strike as a right codified in the state constitution.[47] This is all well and good, but the right of the workers to fight against capitalism, even in the limited form of strikes, should not hinge on the decision of bourgeois politicians. Additionally, the bill itself seems to have been sitting in purgatory since not long after it was introduced, meaning that any sort of legalistic solution to this problem would take much longer than the working class could afford to wait. As the saying goes, direct action gets the goods. Whether striking for public employees is illegal or not, as the material conditions stand, there should be a push for workers in this sphere to be more involved in the strike effort. The power of the proletariat lies in their own actions, not in the bourgeois legislature.[48] With a strong adherence to their principles, even with some going on record as saying they would face arrest and go to jail if it meant they could fight for the betterment of their fellow workers and their students, the 1971 Frankfort-Schuyler Teachers Strike exemplifies this sentiment to a tee.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

-

Unless otherwise noted, newspaper sources are derived from the Fulton History Archives, fultonhistory.com.

↩ -

“The Combination Act of 1800,” Marxists Internet Archive, https://www.marxists.org/history/england/combination-laws/combination-laws-1800.htm.

↩ -

Madeline Will. “Teacher Strikes, Explained: Recent Strikes, Where They’re Illegal, and More.” Education Week. October 30, 2023. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/teacher-strikes-explained-recent-strikes-where-theyre-illegal-and-more/2023/10.

↩ -

“N.Y. Civ. Serv. Law § 210.” Accessed via CaseText. https://casetext.com/statute/consolidated-laws-of-new-york/chapter-civil-service/article-14-public-employees-fair-employment-act/section-210-prohibition-of-strikes.

↩ -

Bob Kelder, “F-S Teachers In 'Rally' to Support Negotiators,” The Evening Telegram, (Herkimer, NY), October 7, 1971.

↩ -

Ibid.

↩ -

Evening Telegram, Oct 14, 1971.

↩ -

Ibid.

↩ -

“FTA 'Crisis Center' Is Opened,” Daily Press, (Utica, NY), October 9, 1971. Based on the available evidence, only the first, second, and sixth steps of this six step plan were revealed in the news.

↩ -

“‘Crisis Center’ In Frankfort,” The Evening Telegram, October 9, 1971.

↩ -

Sources vary with some listing only eight points and others listing up to ten.

↩ -

Remington Rand, Inc., 2 N.L.R.B. 626 (N.L.R.B-BD 1937), 664, https://casetext.com/admin-law/remington-rand-inc-5.

↩ -

Bob Kelder, "Taxpayers Visit Board of Education: Q&A Session At Frankfort," The Evening Telegram, October 12, 1971.

↩ -

“F-S Teachers In 'Rally' to Support Negotiators.”

↩ -

Simona Johnes, "6 Reasons Why School Days Should Be Shorter: Unpacking the Benefits and Challenges of Reduced Classroom Hours," Science and Literacy, https://scienceandliteracy.org/why-school-days-should-be-shorter/; "Shorter School Days: Everything You Need to Know," Juni Learning, August 2, 2023, https://junilearning.com/blog/guide/shorter-school-days-2.; I touch upon the radical history of the fight for a shorter work week in my first article for Cosmonaut. See J.N. Cheney, "Stop the Press, Start Fighting! The 1967 Newspaper Strike in Utica, New York," Cosmonaut Magazine, November 15, 2024, https://cosmonautmag.com/2024/11/stop-the-presses-start-fighting-the-1967-newspaper-strike-in-utica-new-york/.

↩ -

"FSTA Acts To Break Impasse," The Observer-Dispatch (Utica, NY), October 10, 1971.

↩ -

"FSTA Returning to 'Go-Around' Table," The Daily Press, October 13, 1971.; “Meeting Tonight On Teacher Pact." Evening Telegram, October 13, 1971.

↩ -

Art Reagan and Bob Kelder, "Strike Vote By Teachers Assn. At Frankfort," The Evening Telegram, October 14, 1971.

↩ -

Ibid.

↩ -

Ibid.

↩ -

Ibid; "Taxpayers Visit Board of Education: Q&A Session At Frankfort."

↩ -

Bob Kelder and Dick Frosch, "Pickets Patrol As Teacher Strike Begins In Frankfort," The Evening Telegram, October 15, 1971; "Strike Vote By Teachers Assn. At Frankfort."

↩ -

Ibid.

↩ -

"Board Rejects F-S Salary Proposal," The Daily Press, October 16, 1971.

↩ -

"Teachers On Strike," The Evening News (Newburgh, NY), October 16, 1971. https://books.google.com/books?id=netGAAAAIBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

↩ -

Bob Kelder, "NYSTA Support For F-S Teacher Strike," The Evening Telegram, October 16, 1971.

↩ -

"Mediator Drops Out Of Talks," Olean Times Herald (Olean, NY), October 18, 1971.

↩ -

Dick Frosch, "Tentative Agreement Reached: Frankfort Teachers Return," The Evening Times, October 19, 1971; "Frankfort Teachers Reach Agreement," The Times Record (Troy, NY), October 20, 1971.

↩ -

David Colburn, "Frankfort-Schuyler School Board Ratifies Contract with Teachers 6-1." The Daily Press (Utica, NY), October 20, 1971.

↩ -

"Taylor Law Needs Revision," The Daily Press, October 16, 1971.

↩ -

Ibid.

↩ -

John Martin Rich, “A Philosophic View: Civil Disobedience and Teacher Strikes,” The Phi Delta Kappan 45, no. 3 (1963): 151. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20343067.

↩ -

Anne M. Ross, “Public Employee Unions and the Right to Strike,” Monthly Labor Review 92, no. 3 (1969): 15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41837581.

↩ -

Michael Potts, "Quoted Correctly, Rev. Toner Says," The Observer-Dispatch, October 15, 1971.

↩ -

Rich, “A Philosophic View: Civil Disobedience and Teacher Strikes,” 152-153.

↩ -

One article from Jacobin touches upon the revolutionary significance of the US civil rights movement and tools such as civil disobedience. See: Jonah Birch and Paul Heideman, "American Socialists: Study the Civil Rights Movement," Jacobin. February 12, 2024. https://jacobin.com/2024/02/civil-rights-movement-strategy-socialist-politics; Rich. 153.

↩ -

Rich, 154.

↩ -

Ross, “Public Employee Unions and the Right to Strike,” 15-16.

↩ -

Vladimir Lenin, “On Strikes,” 1899, https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1899/dec/strikes.htm.

↩ -

Alex Gourevitch, “Themselves Must Strike the Blow: The Socialist Argument for Strikes and Self-Emancipation,” Philosophical Topics 48, no. 2 (2020): 111. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48652123.

↩ -

Ibid, 111-112.

↩ -

Jaeah Lee and Dana Liebelson, "Map: Wave of New Teacher Strikes Hits Illinois," Mother Jones. September 20, 2012, https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2012/09/map-teacher-strikes-across-united-states/.

↩ -

Paul Wilcox, "The Historic Teachers' Strikes: What Do They Mean?," Liberation News. May 3, 2018, https://www.liberationnews.org/the-historic-teachers-strikes-what-do-they-mean/.

↩ -

Anya Kamentz and Clare Lombardo, "Unionized Or Not, Teachers Struggle To Make Ends Meet, NPR/Ipsos Poll Finds," NPR, May 2, 2018, https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2018/05/02/605757547/unionized-or-not-teachers-struggle-to-make-ends-meet-npr-ipsos-poll-finds; Reggie Wade, "Almost half of teachers work a second job," Yahoo Finance, August 16, 2019, https://finance.yahoo.com/news/half-of-teachers-work-second-job-fishbowl-survey-191713515.html.

↩ -

Jessica Corbett, "Subsidizing Underfunded Schools, US Teachers Spend $459 of Their Own Money Each Year on Classroom Supplies," Common Dreams, August 22, 2019, https://www.commondreams.org/news/2019/08/22/subsidizing-underfunded-schools-us-teachers-spend-459-their-own-money-each-year; Wellington Soares and Caroline Bauman, "Protein Bars, Paper, a Rabbit: What Teachers Buy For Their Classrooms With Their Own Cash," Chalkbeat, October 1, 2024, https://www.chalkbeat.org/2024/10/01/teachers-buying-classroom-supplies-with-their-own-money/.

↩ -

Rachel Cohen, "US Teacher Strikes Were Good, Actually," Vox, August 25, 2024, https://www.vox.com/education/368756/teachers-school-unions-labor-education-students-strikes.

↩ -

PSC-CUNY, "Proposed Amendment to the NY State Constitution Would Give All Employees the Right to Strike!," January 11, 2023, https://psccunygc.commons.gc.cuny.edu/2023/01/11/proposed-amendment-to-the-ny-state-constitution-would-give-all-employees-the-right-to-strike/; The bill as listed on the New York State Senate’s website, https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2023/A906.

↩ -

Robert Ovetz, "Killing the Taylor Law," The Chief, July 11, 2023, https://thechiefleader.com/stories/killing-the-taylor-law,50762.

↩